Let’s get one thing clear: words can hurt.

Imagine you have a friend whose boyfriend just died. Words are really powerful in this situation: they can help communicate your care and empathy for your friend, or they can hurt your friend and cause pain. If you were to say, for instance, that it was your friend’s fault that the boyfriend was dead, those words could have a deep impact—so deep that it might even drive your friend to suicide.

Far more minor word choices could be hurtful as well. For a long while after the tragedy, you would probably try to be sensitive and aware with your language so that you don’t unintentionally cause your friend further pain. You will probably choose not to gush about the guy you’re crushing out on right now. You may decide against inviting your friend to go see that new movie with a sappy love story in it. You might avoid certain topics because you know they will serve as a reminder of the loss.

You wouldn’t do these things because you’re trying to be “correct” or avoid “offending” your friend. You’d do these things because you care about your friend and you’re (hopefully) not a royal jerk.

Sometimes you won’t be able to avoid causing your friend pain. You’ll say that you are totally craving a root beer float right now, and your friend will burst into tears, because that was the boyfriend’s favorite treat. You didn’t know that, so there was no way for you to avoid it. So you apologize—you didn’t do anything wrong but your friend is crying, so you say how sorry you are that something you said brought up a painful memory. And you don’t bring up root beer floats again.

If it seems absurd to accuse someone who is grieving the loss of a loved one of being an authoritarian fascist for asking that people not mention root beer floats around them for a while, then it should seem equally absurd to angrily or dismissively accuse someone who speaks out against racist, sexist, ableist, or otherwise oppressive language of being “politically correct.”

When you hurt someone—for example, by stepping on their toe—you have a choice. You can blame them for getting hurt: “Why was your toe there? You should be more careful about where you put your toes!” You can dismiss their hurt: “Stop being a baby; I barely touched you—you’re too sensitive.” Or you can apologize: “I’m so sorry—I didn’t mean to hurt you. Is there anything I can do?” And you can work on being more aware of people’s toes in the future.

Similarly, when our words cause harm—regardless of our intentions—we have a choice. But only one option will actually create the opportunity for healing: acknowledging the impact of our words, apologizing, and working to be more aware so that we reduce harm in the future.

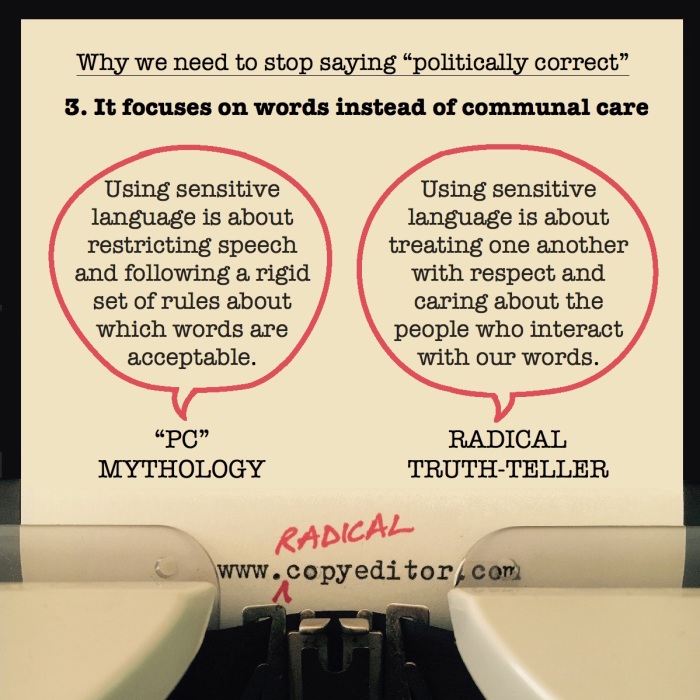

“Politically correct” does not encourage us to care for one another. It communicates a myth that there’s some perfect, one-size-fits-all way to use language that will allow people to move through the world without “offending” or hurting each other, and that the goal is to restrict language to fit this mythical ideal way of speaking and writing.

That’s not how language works. Mentioning root beer floats isn’t universally hurtful, it’s only harmful when it brings up trauma. Language is completely context-specific. Avoiding harm depends entirely on being in relationship and being aware of context, not following a set of rules.

Which brings us to our next point: oppression is some major context.

Read on:

Go back:

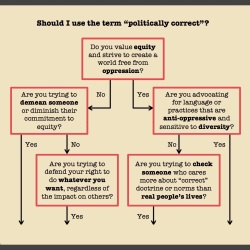

[Description of featured image above: Reason #3 for why we need to stop saying “politically correct”: it focuses on words instead of communal care. “PC” mythology speech bubble says: “Using sensitive language is about restricting speech and following a rigid set of rules about which words are acceptable.” Radical truth-teller speech bubble says: “Using sensitive language is about treating one another with respect and caring about the people who interact with our words.”]